Fact check and tag at the same time, as a contract business?

Fact-Checkers and Certified Public Logicians

It's fantastic that so much written knowledge is becoming generally accessible and cross-linked these days, but this is just an intermediate stage-- a universal library on the way to becoming a universal brain. The missing piece is encoding the underlying meaning of the stored text, the deep-structure logic behind it. It's one of the oldest challenges in Computer Science, and there has been lots of progress and companies dedicated to doing this. Powerset, for example, has software that has parsed and can answer questions from all of Wikipedia.

The thing is, you really still need a person to get it most reliably right, because people understand the way the world works. Luckily, we already have people whose job is very close to doing this already-- they're called fact-checkers or researchers, and they work for every reputable publication.....

I have wondered for years, as magazines, newspapers, and other news organizations have been hemorrhaging money and employees, why someone hasn't gone into the contract fact-checking business. Like, it could be an extension of Snopes.com. There's a huge redundancy in every publication having their own research desks, so they could lay off all of their fact-checkers and then outsource the job to the new, independent company that the best of them then all go to work for. Meanwhile, the company could also be hired by anyone else. Then, when the public sees the "Fact-Checked by MiniTrue (SM)" seal on someone's independent blog, they know the information there has the same credibility as the big boys.

Now, what if these fact-checkers didn't just vet and correct the text? While they dig into the logic and accuracy of everything, as usual, they could also use some simple application to diagram the sentences and disambiguate the semantics into a machine-friendly representation. Just a little extra clicking, and they could bind all the pronouns to their antecedents, and select from a dropdown box to specify whether an instance of the string "Prince" refers to the musician Prince or to Erik Prince-- the president of XE, the company formerly known as Blackwater-- within an article that for whatever reason mentions both of them.

Then you would really have something. The text wouldn't just be fact-checked; its underlying meaning could be added into a shared pool of human knowledge, chained through, verified or denied, and used in other ways by any technology that may now exist or may exist in the future.

Taxonomies and tags are political, or #Amazonfail

Complaints, firestorms on Twitter, blog posts, and general mayhem ensued. Many people thought it was an act of out and out bias, especially since gay marriage in the states has been a big newsmaker in this last month. Authors asked Amazon what was going on, and received a tepid response. Evidently the powers that be at Amazon had decided to no longer display books tagged with the "adult" tag in their rankings anymore. And somehow, this "adult" tag included books like Heather has Two Mommies and Lady Chatterley's Lover, not just adult books. It meant that if you searched on "homosexuality", your searches would only reveal anti-homosexuality books and items. Several blogs took screen captures and posted them. Many people went into Amazon's book listings and started tagging books with #amazonfail. User tagging as a protest tool! Twitter posts quickly spread with the #amazonfail tag as well.

After reading a ton of articles and postings about this mess, I think I agree with Patrick at Making Light:

I’d bet lunch that the sequence of events, in its simplest form, went something like this:

(1) Sometime in the middle-distance past—maybe a couple of months ago, maybe a year, it doesn’t matter—somebody decided that it would be a good idea to make sure that works of straight-out pornography (or, for that matter, sex toys) didn’t inadvertently show up as the top result for innocuous search queries. (The many ways that this could happen are left as an exercise for Making Light’s commentariat.) A policy was promulgated that “adult” items would be removed from the sales rankings and thus rendered invisible to general search.

(2) Sometime more recently, an entirely different group of people were given the task of deciding what things for sale on Amazon should be tagged “adult,” but in the journey from one department to another, and from one level of the hierarchy to another, the directive mutated from “let’s discreetly unrank the really raunchy stuff” to “we’d better be careful to put an ‘adult’ tag on anything that could imaginably offend anyone.” Indeed, as Teresa pointed out, it’s entirely possible that someone used a canned list of “adult” titles supplied from outside, something analogous to the lists of URLs sold by “net nanny” outfits, which would account for the newly-unranked status of works like Lady Chatterley’s Lover. (As one net commenter observed, “What is this, 1928?”)

I have found when doing taxonomy that it is an activity with almost no neutral ground. Every decision has its opponents, and you have to build consensus for a particular worldview when you are working with groups who see the world differently, and that's nearly every group of more than two people. I was working in a relatively calm area like PC hardware or software tasks, where you would think a printer and a monitor are not the same category of item, and yet I heard arguments that were valid showing me why they were the same! "It depends," as we always say about indexing.

Things are starting to get fixed. Some recent searches under homosexuality on Amazon were starting to show more normal results, so I think the #amazonfail tagging effort has had some effect and Amazon is doing something about this, after their feeble first response. The Seattle PI has a response from Amazon's Drew Herdener:

This is an embarrassing and ham-fisted cataloging error for a company that prides itself on offering complete selection.

It has been misreported that the issue was limited to Gay & Lesbian themed titles – in fact, it impacted 57,310 books in a number of broad categories such as Health, Mind & Body, Reproductive & Sexual Medicine, and Erotica. This problem impacted books not just in the United States but globally. It affected not just sales rank but also had the effect of removing the books from Amazon's main product search.

Many books have now been fixed and we're in the process of fixing the remainder as quickly as possible, and we intend to implement new measures to make this kind of accident less likely to occur in the future.

Amazon does need to look at its taxonomy structures and labeling, and see where they might be failing. You cannot let machine algorithms replace human sensibility. I think Amazon is importing tags from publishers, and probably importing taxonomies. At a session years ago I heard from an employee that they let all of their fact-checking people go, and rely on users and publishers to supply correct and corrected data on all of their bibliographic information. It saved them 400 jobs. Libraries I knew had stopped their subscriptions to Books In Print, thinking Amazon would be easier and faster and just as good, not realizing that it is full of errors until corrected. We have all seen examples of wrong covers for books, or indexes for the first edition showing up in the second edition's listings. I would bet they are relying on publishers for taxonomic structures as well, but I don't know for sure. Probably piecemeal, using them in places, finetuning them in others.

As Laura Dawson says:

I've done so much taxonomy work, both for Muze and BN.com - and my colleagues and I have all agonized over the political decisions we've had to make because in a taxonomy you have to articulate concepts and arrange them. Like staying-awake-at-night agonizing, because these articulations and arrangements either bring books to light or tuck them away where few can find them, depending. (Richard Nash also makes a great point up this same alley.)

And it's worth getting upset about. What happened at Amazon is the result of dozens of small decisions about how to name things and the structure of those names - whether the decisions were made by people at Amazon or they were importing other companies' taxonomies (probably both) or using semantics to create algorithms. Shirky is right in that it probably wasn't a person or group of people deciding that they didn't like gay people that day. But (as Richard points out) it was the result of heteronormative thinking creating search rules that ultimately resulted in...#amazonfail.

What taxonomizing teaches you is that no worldview is neutral, and the best you can hope for is to keep trying to reach in that direction. Detangling what happened at Amazon is compounded by the fact that they aren't talking to anyone, but it appears to be a compilation of complacent taxonomizing, linking certain concepts to the theme "adult", imposing some sort of filter on the "adult" titles (without realizing what "adult" meant in terms of the terms that linked to it) in a misguided effort to make explicit books less visible, not fully investigating the problem when it first came to Amazon's attention (but dismissing it as a "policy" decision, which is most likely never was in the first place), and now not really responding effectively. Probably because those in charge of responding really have no idea how it happened.

Laura wrote that last bit before Amazon's second response.

Taxonomies and tags are political. Indexing is political. Labeling structures are political. So I wonder what tags I'll use to categorize this post - ;-)

If you want to read up on what happened, and many people's responses, here's a list of blog postings:

Laura Dawson

Clay Shirky

Mary Hodder

Richard Eoin Nash

Jane at Dear Author

Bruce Sterling on tagging and Web 2.0

Let's look at a few of these Web 2.0 principles and practices.

"Tagging not taxonomy." Okay, I love folksonomy, but I don't think it's gone very far. There have been books written about how ambient searchability through folksonomy destroys the need for any solid taxonomy. Not really. The reality is that we don't have a choice, because we have no conceivable taxonomy that can catalog the avalanche of stuff on the Web. We have no army of human clerks remotely able to tackle that work. We don't even have permanent reference sites where we can put data so that we can taxonomize it....

"Dynamic content." Okay, content is a stable substance that is put inside a container. It's stored in there: that's why you put it inside. If it is dynamically flowing through the container, that's not a container. That is a pipe. I really like dynamic flowing pipes, but since they're not containers, you can't freakin' label them!

There's a lot more, about the next thing, which he calls the Transitional Web. Worth the read.

Gene Smith on tagging

It's worth taking a look even without any notes. Highly recommended book, too.

Tagging vs. indexing

Here's a new study analyzing tagging practices. Is this "indexing by mob" or is it a valuable source of vocabulary?

PS. I really really recommend this book.

The death of taxonomy?

On this

first day of 2009, I thought I’d take a moment to

reflect on the CMS Watch list of predictions for

2009. Getting big play in the top 3 is “Taxonomies

are dead. Long live metadata!”

"With social computing coming to the fore, it’s never

been more obvious that everyone does not, and will

never, categorize things in the same way. It doesn’t

even matter what’s correct anymore… I will assert

that the days of the traditional, definitive, and

single-hierarchy taxonomy are long behind us."

I think that this is accurate — insofar as it uses

the traditional, definitive and single-dimension

definition of taxonomy that ought to be left in the

dust along with corded telephones and dot matrix

printers. I mean, I can’t even remember ever building

a taxonomy that was meant to be traditional or had a

single-hierarchy.

The term “taxonomy” has grown to mean so much more

than this… We use taxonomy in a very broad sense -

suggesting that all metadata comes from the taxonomy.

Everything is about classification and structure.

Certainly “taxonomy” has become an abused term. They

say taxonomy when they want their information world

to be a better place. There is a comforting, ordered

ring to the term. It sets all things in the world in

their proper place.

There's a lot more Stephanie talks about, how business people don't get metadata, and how the term taxonomy is evolving, not dying - I highly recommend reading the post and the blog when you can! There are a lot of great articles in the archives as well.

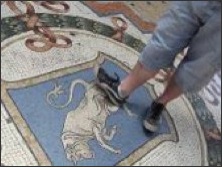

Do tags work? By Cathy Marshall

An entertaining study of photo tags on Flickr reveals user tags to be somewhat, um, lacking... In a study of photos of a mosaic of a bull in Milan, one that has a good luck ritual associated with it, Marshall found taggers tagging photos with retrievability-hampered results. In other words, the average joe isn't very good at tagging, even for their own data.

The message

here is almost painful: a great proportion of user

tags add little or no further information; as such,

they don't appear as often in narratives or titles.

Personal names, which may be quite useful for finding

photos among one's own collection (especially over

the long haul) are less well represented in all types

of metadata, but are relatively similar in quantity.

Now here's a property of tags that I find almost

comical: they are seldom verbs, even if a verb is

just the thing to characterize a photo. What's unique

about what tourists do when they visit the Galleria's

bull mosaic? They spin. In fact, if you type in Milan

spin as your Flickr search terms, you pull up 94

results, 70 of which are pictures of our bull mosaic.

20 out of 24 results on the first page are on target.

Although spin and spinning make the top 20 list of

tags, they are by no means commonly used terms; they

are used less than 1% of the time (0.7%). That's just

7 tags. On the other hand, spin makes up 4.8% and

9.5% of title and narrative terms. People just don't

seem to be thinking of tags as verbs.