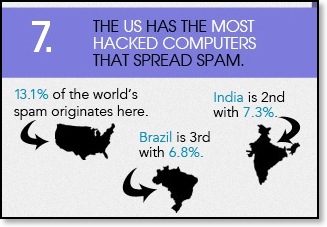

Where people are moving

06/17/10 11:06 Filed in: miscellany

Cool interactive map of where people are moving to and from on a county and city basis. Check out your county at Forbes

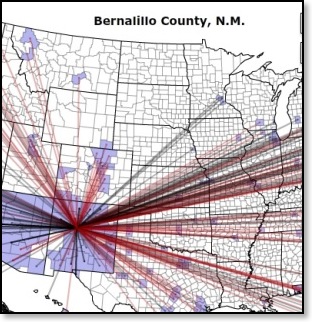

Nice library, and it includes the hand from the Addams Family

06/14/10 11:02 Filed in: books

Internet entrepreneur Jay Walker used his fortune to create an elaborate library filled with intellectual achievements spanning human history.

This private library is 3,600 square feet filled with landmark and

bejeweled books, an early edition of Chaucer, a small earth globe signed

by nine astronauts, a 300-million-year old trilobite fossil, the

original hand prop from the TV show The Addams Family, a hand-painted

“celestial atlas” from 1660, an original copy of The Nuremberg Chronicle

from 1493, a working version of a Nazi-era Enigma machine, an original

Sputnik 1 satellite hanging from the ceiling, a chandelier from a James

Bond film, the napkin that Roosevelt sketched out his plan for victory

in 1943, a field tool kit for Civil War surgeons, all encompassed in

three levels packed with more rare artifacts than your local history

museum.

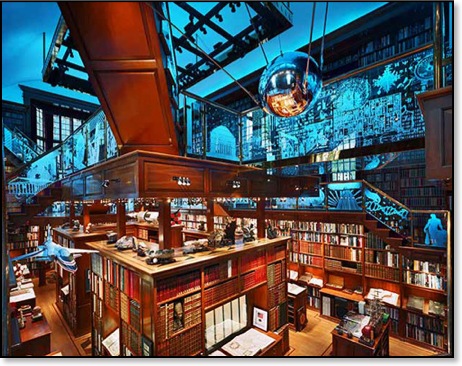

Books as databases

06/11/10 11:00 Filed in: books

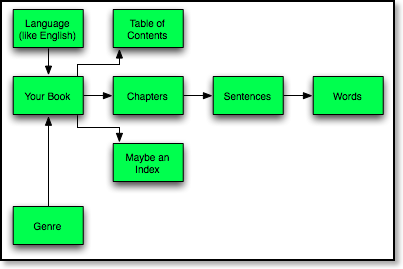

So

what would a relational database of a book look like

in diagram form? Somewhat similar. Like this:

The book is the anchor of this relational database much like the recipe box is in the recipe box example. Inside the book: chapters, a table of contents, maybe an index. Each chapter is made up of sentences (at least sentences…maybe pictures, too!) and each sentence is made up of words.

What is this "maybe an index" bit?

Here's a bit more from Chris Kubica at Publishing Perspectives:

Writing/building a book-as-database from the start requires thinking about how the contents of a book can later be searched, shared, aggregated, re-organized, re-presented, re-purposed and indexed.

However, the interface for readers and even for the author need not be complex or extra-technical in the slightest. A writer could write the book the “old fashioned way”, using a word processor and then upload the manuscript to be “processed” into database format by the publishing platform (more on platforms later). Or a writer could simply write rightin a Web browser while the platform automatically saves the work regularly into book-as-database format.

The book is the anchor of this relational database much like the recipe box is in the recipe box example. Inside the book: chapters, a table of contents, maybe an index. Each chapter is made up of sentences (at least sentences…maybe pictures, too!) and each sentence is made up of words.

What is this "maybe an index" bit?

Here's a bit more from Chris Kubica at Publishing Perspectives:

Writing/building a book-as-database from the start requires thinking about how the contents of a book can later be searched, shared, aggregated, re-organized, re-presented, re-purposed and indexed.

However, the interface for readers and even for the author need not be complex or extra-technical in the slightest. A writer could write the book the “old fashioned way”, using a word processor and then upload the manuscript to be “processed” into database format by the publishing platform (more on platforms later). Or a writer could simply write rightin a Web browser while the platform automatically saves the work regularly into book-as-database format.

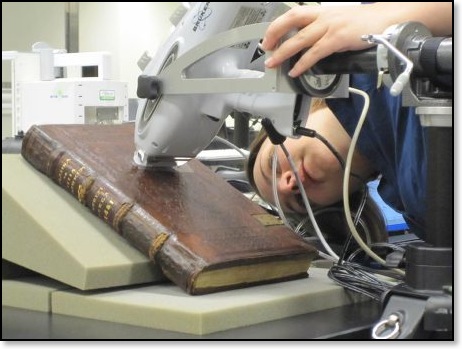

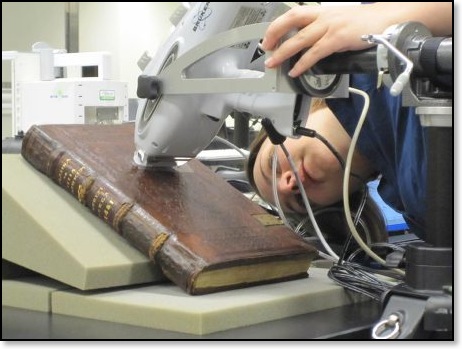

Digitizing the past at the Library of Congress

06/10/10 10:59 Filed in: books

"It's

incredible, it's humbling. It might be 6 p.m. and

I'll be exhausted but I think, 'I can't complain--I'm

working with the Gettysburg Address!'"

The Library of Congress has nearly 150 million items in its collection, including at least 21 million books, 5 million maps, 12.5 million photos and 100,000 posters. The largest library in the world, it pioneers both preservation of the oldest artifacts and digitization of the most recent--so that all of it remains available to future generations.

Amazing collection of photos of their work here. Great rewinding equipment for various kinds of tape, x-ray machines, and other methods of collecting data from fragile items.

The Library of Congress has nearly 150 million items in its collection, including at least 21 million books, 5 million maps, 12.5 million photos and 100,000 posters. The largest library in the world, it pioneers both preservation of the oldest artifacts and digitization of the most recent--so that all of it remains available to future generations.

Amazing collection of photos of their work here. Great rewinding equipment for various kinds of tape, x-ray machines, and other methods of collecting data from fragile items.

Most misspelled words on Google

06/07/10 10:56 Filed in: silliness

The

examples of misspellings that Google sees most often

are typos of very frequently searched terms, such as

“Criagslist” instead of “Craigslist” and “Facebok”

instead of “Facebook.” But Mr. Paskin

said words

that aren’t spelled the way they sound also give

people trouble.

He cited a few of the most common examples:

* “definitely,” which is often spelled “definately,” “definetly” or “definatly”* “stilettos,” which people spell “stilletos,” and “stillettos”* “mischievous,” spelled “mischevious” and “mischievious” and* “nauseous,” which comes out “nautious,” “nauseas” and “nausious.”

Stilettos? Really, is that a most used term?

More here at the WSJ

He cited a few of the most common examples:

* “definitely,” which is often spelled “definately,” “definetly” or “definatly”* “stilettos,” which people spell “stilletos,” and “stillettos”* “mischievous,” spelled “mischevious” and “mischievious” and* “nauseous,” which comes out “nautious,” “nauseas” and “nausious.”

Stilettos? Really, is that a most used term?

More here at the WSJ

The web shatters your focus

06/04/10 10:54 Filed in: reading

Navigating

linked documents, it turned out, entails a lot of

mental calisthenics—evaluating hyperlinks, deciding

whether to click, adjusting to different formats—that

are extraneous to the process of reading. Because it

disrupts concentration, such activity weakens

comprehension. A 1989 study showed that readers

tended just to click around aimlessly when reading

something that included hypertext links to other

selected pieces of information. A 1990 experiment

revealed that some “could not remember what they had

and had not read.”

Even though the World Wide Web has made hypertext ubiquitous and presumably less startling and unfamiliar, the cognitive problems remain. Research continues to show that people who read linear text comprehend more, remember more, and learn more than those who read text peppered with links. In a 2001 study, two scholars in Canada asked 70 people to read “The Demon Lover,” a short story by Elizabeth Bowen. One group read it in a traditional linear-text format; they’d read a passage and click the word next to move ahead. A second group read a version in which they had to click on highlighted words in the text to move ahead. It took the hypertext readers longer to read the document, and they were seven times more likely to say they found it confusing. Another researcher, Erping Zhu, had people read a passage of digital prose but varied the number of links appearing in it. She then gave the readers a multiple-choice quiz and had them write a summary of what they had read. She found that comprehension declined as the number of links increased—whether or not people clicked on them. After all, whenever a link appears, your brain has to at least make the choice not to click, which is itself distracting.

There's lots more, and it is astonishing, at Wired....

Even though the World Wide Web has made hypertext ubiquitous and presumably less startling and unfamiliar, the cognitive problems remain. Research continues to show that people who read linear text comprehend more, remember more, and learn more than those who read text peppered with links. In a 2001 study, two scholars in Canada asked 70 people to read “The Demon Lover,” a short story by Elizabeth Bowen. One group read it in a traditional linear-text format; they’d read a passage and click the word next to move ahead. A second group read a version in which they had to click on highlighted words in the text to move ahead. It took the hypertext readers longer to read the document, and they were seven times more likely to say they found it confusing. Another researcher, Erping Zhu, had people read a passage of digital prose but varied the number of links appearing in it. She then gave the readers a multiple-choice quiz and had them write a summary of what they had read. She found that comprehension declined as the number of links increased—whether or not people clicked on them. After all, whenever a link appears, your brain has to at least make the choice not to click, which is itself distracting.

There's lots more, and it is astonishing, at Wired....

Librarians do Lady Gaga

06/02/10 10:51 Filed in: silliness

See the whole thing here

It's the UW Library School, with many featured cameos - Nancy Pearl, Bob Boiko, etc.