At the top of the page, you see a navigation bar with broad topics. Breaking information into broad chunks for a web page is much like providing a table of contents. This is a "top down" findability device. As long as you (the reader) thinks in the same categories as the developer of the information does, you will find things quickly with a navigation bar or table of contents. But if you are thinking in different ways, this may not be your most effective tool. Navigation bars and tables of contents help people take a top down approach, and explore and drill down into information. They are exploratory.

But let's say you aren't in an exploratory mode of information gathering. You want to know a specific fact, such as whether or not Wright Information does embedded indexing. You may not know whether to look in "credentials", under "software", or under "rates" to find that specific piece of information. Some common findability tools can help: a sitemap, a site search bar and the index. A sitemap acts as a table of contents, and you have to scan the whole thing to guess where we talk about embedded indexing. If you used a search engine, it would give you results for each page in the world that talks about embedded indexing, and that may be too much information to wade through. The index will show you that indeed, yes, there's information here, on this specific website, about embedded indexing.

Which works better? It depends on the size of the body of information you are searching. In a small site, all these tools will get you to what you need quickly. But let's say you have a grammar site, and you want to look up when to use the word "which" and when to use the word "that." The search engine will not help you, the site map may show an extremely large multi-branched site with too many places to look; you need an analyzed index to get you the precision you want.

On many websites, you see "bread crumbs" - a method of telling you where you are in a site. These are often used to help navigate taxonomies. They are a means of showing you where in a hierarchy of terms or pages you are, and lets you know the next broadest category upward. This is usually helpful. People have a much easier time thinking of subdivisions, and have a much harder time thinking upwards to a next broader topic. Implementing a taxonomy and displaying portions of it to a user gives them not only their location, but hints of what the next higher topic might be, as well as subdivisions beneath and related terms that are equal in stature.

An example of bread crumbs:

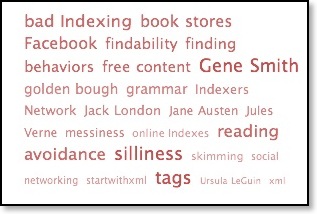

On many sites, you can see the implementation of a tag cloud and categories. These are implemented by tagging the blog posts with a category and descriptors. The cloud shows the number of uses for a particular term by making it larger, and you can easily view all the posts for a tag by clicking on it. If multiple people were feeding tags into the system, you would have a folksonomy - a tool that takes everyone's labels and merges them together. Folksonomies are powerful tools for gathering data on content by using a group approach, gathering all kinds of user terminology, and leveraging the labor. At some point folksonomies become chaotic, and a more controlled vocabulary will be needed. Folksonomies are a good method for feeding a controlled vocabulary, with new terms and variations that one person alone might not have thought of.

An example of a tag cloud:

Metadata is data embedded into a file or content that contains crucial information about the document or content: its author, expiration date, title, publication date, and subject to name a few categories. There are standards for metadata tagging, such as the Dublin Core, but companies often develop their own metadata schemas and systems. Indexing data that is embedded or attached to content is one source of for subject metadata, and can enhance searching and retrieval. To quote a favorite meme:

Contact Wright Information at jancw@wrightinformation.com.